|

|

| |

Iron County |

| |

This report provides the most current

information and data found, as of May 2007, unless

otherwise noted. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

SOURCES

OF DRINKING WATER

Wisconsin enjoys a generally clean

and abundant groundwater resource.A2 This resource is present because of the

state’s geologic history and climate; this resource is protected

through strong state and federal regulations, and the cooperative efforts of

water systems, trade associations, individual operators, planning commissions,

and state and federal science agencies.

Drinking water in Wisconsin is provided

by either public water systems or private wells. A public water system is defined

as a system that provides public water for human consumption, if such a system

has at least 15 service connections or regularly serves an average of at least

25 individuals daily at least 60 days out of the year. Wisconsin has nearly 11,500

public water systems which meet the daily water needs of about 4 million people.A1 The Wisconsin

Department of Natural Resources (WDNR)A3 oversees

these public systems, and additional information can be found online.

Public water systems that are owned by a community are called municipal

water systems.A4 Iron

County has 5 municipal water systems.

In addition to the public water systems, about 850,000

private wells provide drinking water to Wisconsin's population. Unlike public

water systems, protection and maintenance of a private well is largely the responsibility

of homeowners. Information on how to build and protect your private water supply

can be found on the WDNR

web site.A5 The USGS

is finalizing the "Summary of Water

Use in Wisconsin for 2005." When released, this summary will show the percentage

of the Iron County population whose drinking water comes from private wells versus

municipal systems.

return to top

|

| |

GROUNDWATER

PROTECTION POLICIES

WELLHEAD PROTECTION PLANS AND ORDINANCES

- 1 of 5 municipal water systems in Iron

County has a wellhead protection plan: Mercer.B1

- 1 of 5 municipal water systems in Iron

County has a wellhead protection ordinance: Mercer.B1

|

For recommendations of groundwater protection policies

and some outstanding examples of innovative groundwater protection policies adopted

by other communities see Groundwater

Protection Policies.

|

|

Wellhead protection plans are developed to achieve

groundwater pollution prevention measures within public water supply wellhead

areas. In some areas of the state, sophisticated groundwater flow modeling techniques

were used to delineate source

water areas for municipal wells. A wellhead protection

plan uses public involvement to delineate the wellhead protection area, inventory

potential groundwater contamination sources, and manage the wellhead protection

area. All new municipal wells are required to have a wellhead protection plan.

A wellhead protection ordinance is a zoning ordinance that implements the wellhead

protection plan by controlling land uses in the wellhead protection area.B2

Of those municipal water systems that have wellhead

protection (WHP) plans, some have a WHP plan for all of their wells, while others

only have a plan for one or some of their wells. Similarly, of those municipal

water systems that have WHP ordinances, some ordinances apply to all of their

wells and others just one or some of their wells.

ANIMAL WASTE MANAGEMENT ORDINANCES

- Iron County has

not adopted

an animal waste management ordinance.B3

Most Wisconsin counties have adopted an animal waste

management ordinance that applies to all unincorporated areas of the county

(areas outside of city and village boundaries). While the purposes of such ordinances

vary among counties, a key purpose is often to protect the groundwater and surface

water resources. This is accomplished by regulations such as:

- Permitting of animal waste storage

facilities;

- Permitting of new and expanding feedlots;

- Nutrient management;

- Prohibiting:

- Overflow of manure storage structures;

- Unconfined manure stacking or piling

within areas adjacent to stream banks, lakeshores, and in drainage channels;

- Direct runoff from feedlots or stored

manure to waters of the state;

- Unlimited livestock access to waters

of the state where high concentrations of animals prevent adequate sod cover

maintenance.

More information is available from the WDATCP.

ADDITIONAL GROUNDWATER PROTECTION POLICIES

Your county may have additional policies in place

for groundwater protection. A good way to find out is to check with the county

conservationist and local zoning administrators.

return to top

|

| |

MONEY

SPENT ON CLEANUP

PETROLEUM ENVIRONMENTAL CLEANUP FUND AWARD

- Over $4 million

has been spent in Iron County on petroleum cleanup from leaking underground

storage tanks, which equates to $769 per county

resident.C2

The Petroleum Environmental Cleanup Fund Award (PECFA)

program was created in response to enactment of federal regulations requiring

release prevention from underground storage tanks and cleanup of existing contamination

from those tanks. PECFA is a reimbursement program returning a portion of incurred

remedial cleanup costs to owners of eligible petroleum product systems, including

home heating oil systems.C1

As of May 31, 2007, $4,997,735 has

been reimbursed by the PECFA fund to clean up 38 petroleum-contaminated

sites in Iron County. This equates to $769 per

county resident, which is greater

than the

statewide average of $264 per resident.C2

NITRATE REMOVAL SYSTEMS

- No municipal

water systems in

Iron County have spent money to reduce nitrate levels.

As of 2005, over 20 municipal water systems in Wisconsin

have spent over $24 million reducing nitrate concentrations in municipal water

systems.C3

return to top

|

| |

GROUNDWATER

USE

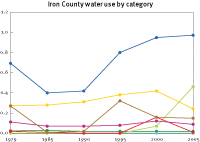

- From 1979 to 2005, total water use in Iron County has increased from about

400,000 gallons per day to about 970,000 gallons per day.*

- The increase in total water use is due primarily to increases in irrigation

and public use and losses.

- The proportion of county water use supplied by groundwater has been consistently

100% for the period 1979 to 2000 and decreased sharply to 56% in 2005.*

As part of the National Water-Use Information Program,

the USGS stores water-use data in standardized format for different categories

of water use. In 1978, the USGS entered into a cooperative program with the WDNR

to inventory water use in Wisconsin. Since that time, five reports summarizing

water use have been published (Lawrence and Ellefson, 1982D2;

Ellefson and others, 1987D3;

Ellefson and others, 1993D4;

Ellefson and others, 1997D5;

Ellefson and others, 2002D6;

Buchwald and others, 2008D7).

Water use in Wisconsin in these summary reports is

reported in the following categories: domestic, livestock, aquaculture, industrial,

commercial, public use and losses, thermoelectric or mining. References describing

the methods for collecting data and estimating water use are provided in the

summary reports.

* Thermoelectric and mining data are not

considered in water-use tables or figures on this web site. Thermoelectric-power

water use is the amount of water used in the process of generating thermoelectric

power. The predominant use of water is as non-contact cooling water to condense

the steam created to turn the turbines and generate electricity. D1

return to top

|

| |

SUSCEPTIBILITY

OF GROUNDWATER TO CONTAMINANTS

In Wisconsin, 70% of residents and 97% of communities rely on groundwater

as their drinking water source. Wisconsin has abundant quantities of high-quality

groundwater, but once groundwater is contaminated, it's expensive

and often not technically possible to clean. Because of these factors, we need

to be careful to protect our groundwater from contamination. Our activities

on the land can contaminate groundwater - most contaminants originate on the

land surface and filter down to the groundwater. In some cases however,

groundwater can become contaminated from natural causes such as radioactivity

due to the presence of radium in certain types of rocks.

READ

MORE ABOUT SUSCEPTIBILITY

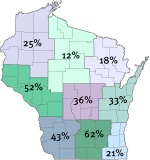

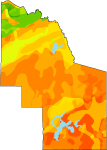

“Susceptibility of Groundwater to Pollutants” is defined here as the ease with which a contaminant can be transported from the land surface to the top of the groundwater called the “water table”. Many materials that overlie the groundwater offer good protection from contaminants that might be transported by infiltrating waters. The amount of protection offered by the overlying material varies, however, depending on the materials. Thus, in some areas, the overlying soil and bedrock materials allow contaminants to reach the groundwater more easily than in other areas of the state.

In order to identify areas sensitive to contamination, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin-Extension, Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey and the USGS, has evaluated the physical resource characteristics that influence this sensitivity.

Five physical resource characteristics were identified as important in determining how easily a contaminant can be carried through overlying materials to the groundwater. These characteristics are depth to bedrock, type of bedrock, soil characteristics, depth to water table and characteristics of surficial deposits. Existing statewide maps of these five characteristics were used whenever possible. New maps were compiled when existing information wasn’t already mapped. The resource characteristic maps used in this project were compiled from generalized maps at a scale of 1:250,000 or 1:500,000.

Each of the five resource characteristic maps was put into digital form using a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) program. All of the information contained in the five maps were overlaid and combined into one composite map. A numeric rating scheme developed for each map was used to score the maps and the five resource map scores were added together within GIS. The composite map shows the scores for each area – low scores represent areas that are more susceptible to contamination and high scores represent areas that are less susceptible to contamination.

The method described above is a subjective rating method; specifically an index method. An index method assigns a subjective ratings or score to physical resource characteristics of an area to develop a range of contamination susceptibility categories (ranging, in this case, from more susceptible to less susceptible). Index methods are fairly popular approaches to groundwater susceptibility, because they are quick and straightforward, and they use data that are readily available. However, the mapped distribution of susceptibility categories produced by an index method is typically fraught with uncertainty, primarily due to the subjectivity in the approach. The susceptibility categories include little quantifiable or statistical information on uncertainty and this limits their use for defensible decision making. So while susceptibility maps produced using index methods can be useful, their inherent uncertainty must be kept in mind. (National Research Council, 1993E1; Focazio and others, 2002E2).

return to top

|

| |

GROUNDWATER

QUALITY

NITRATE

- 100%

of 67 private

well samples collected in Iron County from 1990-2006 met the health-based drinking

water limit for nitrate-nitrogen.

Of the 67 samples that have

been collected in the county, 5 samples (7%) contained between 2 and 10 mg/L

(milligrams per liter, or parts per million) nitrate-nitrogen, and serve as indicators

that land use has likely affected groundwater quality. No samples exceeded the

health-based drinking water limit of 10 mg/L nitrate-nitrogen.F1

As shown in the map on the right, there are no samples

where nitrate-nitrogen levels were elevated.F2

Introduction and Sources of Nitrate

In 2006, the WDNR and the Wisconsin Department of

Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (WDATCP) reported that nitrate-nitrogen

(NO3-N) is the most widespread groundwater contaminant in Wisconsin,

and that the nitrate problem is increasing both in extent and severity.F3 In

Wisconsin's groundwater, 80% of nitrate inputs originate from manure spreading,

agricultural fertilizers, and legume cropping systems.F4 On-site wastewater

systems (septic systems) can also be a significant nitrate source in densely

populated areas, areas where fractured bedrock is near the surface, or areas

with coarse-textured soils.F5

Concentrations of nitrate-nitrogen in private water

supplies frequently exceed the drinking water limit (federal and state Maximum

Contaminant Level, or MCL) of 10 mg/L. In 2005, the WDNR combined data from three

statewide groundwater databases and found that 11.6% of 48,818 private wells

exceeded the nitrate limit.F3

Land

use affects nitrate concentrations in groundwater. As shown in the figure on

the right, an analysis of over 35,000 Wisconsin drinking water samples found

that drinking water from private wells was three times more likely to be unsafe

to drink due to high nitrate in agricultural areas than in forested areas. High

nitrate levels were also more common in sandy areas where the soil is more

permeable.F6 Groundwater

with high nitrate from agricultural lands is more likely to contain pesticides

than groundwater with low nitrate levels.F7 Land

use affects nitrate concentrations in groundwater. As shown in the figure on

the right, an analysis of over 35,000 Wisconsin drinking water samples found

that drinking water from private wells was three times more likely to be unsafe

to drink due to high nitrate in agricultural areas than in forested areas. High

nitrate levels were also more common in sandy areas where the soil is more

permeable.F6 Groundwater

with high nitrate from agricultural lands is more likely to contain pesticides

than groundwater with low nitrate levels.F7

Health effects of nitrate

READ MORE

Human health is the primary reason high levels of

nitrate in drinking water are of concern.F3 Nitrate can cause a condition

called methemoglobinemia, or “blue-baby syndrome,” in infants under

six months of age. Nitrate in water used to make baby formula converts to nitrite

in the child’s stomach and changes the hemoglobin in blood to methemoglobin.

The infant’s body is then deprived of oxygen. In extreme cases, methemoglobinemia

can be fatal; the long-term effects of lower-level oxygen deprivation are unknown.

The conversion of nitrate to nitrite in the human

body also creates N-nitroso compounds, which are some of the strongest carcinogens

known. As a result, additional human health concerns linked to nitrate-contaminated

drinking water include increased risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomaF8,

gastric cancerF9, E10, and bladder and ovarian cancer in older women.F11 There

is also growing evidence of a correlation between nitrate and diabetes in children.F12,

E13 The current drinking water limit of 10 mg/L for nitrate-nitrogen addresses

only methemoglobinemia; the concentration at which cancer risks occur is unknown.

Ecosystem effects of nitrate

READ MORE

Nitrate also affects surface water ecosystems by increasing

the growth of nuisance algae that then die and deplete the water of oxygen. Between

the late 1960s and the early 1980s, nitrate levels in waters flowing into the

Gulf of Mexico more than doubled, causing a “dead zone” that in 1999

was approximately the size of the state of New Jersey.F14 In Wisconsin,

the effects of increasing nitrate levels in surface waters are mostly unstudied.

Solutions

READ MORE

Because of the health concerns, public water supplies

that exceed the 10 mg/L limit are required to reduce the nitrate-nitrogen level.

The most common solutions include drilling a new, usually deeper, well; blending

contaminated water with non-contaminated water to lower the nitrate concentration;

or removing nitrate through water treatment processes. However, such solutions

are often costly. By 2006, 25 Wisconsin public drinking water systems had exceeded

the nitrate limit and collectively spent over $24 million on remedies. This number

is up sharply from just 14 in 1999.F3 For information about which

public drinking water systems exceeded the nitrate limit see Money

Spent on Cleanup.

The Wisconsin Well Compensation fund can assist a

private well owner if the nitrate level in his or her well exceeds 40 mg/L (four

times the human health limit), but only if the well is used for livestock watering.

Options for private well owners include replacing or modifying the well, connecting

to a public water supply, installing a water treatment system, or using bottled

water for cooking and drinking.F3

Private well water testing and education programs

offered by the University of Wisconsin – Extension have been successful

in increasing both public awareness of individual nitrate problems and local

government officials’ interest in taking proactive planning steps to protect

groundwater. In Iowa County, for example, town officials began using groundwater

information collected through such programs as criteria for siting new facilities

and developments.F15

Many educational programs have also been put in place

to help farmers limit the loss of nitrogen to groundwater. These programs emphasize

soil testing and proper crediting of nitrogen sources already in place to avoid

overfertilization, and good management practices for fertilizer storage and handling

to minimize spills and other losses. However, numerous researchers have shown

that in central Wisconsin, such best management practices are not always adequate

to prevent contamination of groundwater with nitrate above the drinking water

limit.F16, E17

Recent research on Wisconsin farms has shown that

cattle raising using management intensive grazing (also known as rotational grazing

or grass-fed agriculture) has potential for protecting groundwater from nitrate

contamination.F18 In general, well-managed organic farming practices

also lower nitrate inputs to groundwater,F19, E20 but at times, leaching

from organic systems may also exceed the drinking water limit for nitrate.F21

Some local governments have been successful with

providing incentives to farmers to grow groundwater-friendly crops or otherwise

limit nitrogen applications around city wells. For example, the city of Waupaca

identified fields in the recharge area for its wells and provided various incentives

for farmers to enter into cropping agreements to limit nitrate inputs.F22 A

community may choose to hire a specialist to evaluate nitrate-susceptible areas

and develop possible management strategies.

In addition, three rules currently being proposed

or implemented could decrease nitrate contamination of groundwater:F3

- NR243 (finalized and to be promulgated

in spring 2007) lowers nitrogen levels reaching groundwater from manure and process

wastewater by requiring improved manure storage facilities and prohibiting excessive

or improper application of manure and process wastewater on cropped fields. This

rule will apply to large Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations of 1000 animal

units and larger. Currently, there are about 150 of these permitted operations

in Wisconsin.

- ATCP51 (enacted in April 2006) is a

livestock siting standard that protects areas susceptible to groundwater pollution.

Required standards prevent runoff from entering sinkholes, ensure that existing

storage structures do not leak, and require a manure application plan that minimizes

risks to groundwater, including existing wells. This adopted rule is expected

to apply to about 70 new and expanding farms of more than 500 animal units each

year.

- ATCP50 (still pending as of April 2007)

applies to all farms and includes the requirement for nutrient management plans

by 2008. It incorporates new 2005 USDA NRCS nutrient standards (590 standards)

for both nitrogen and phosphorus application.

Planning

READ MORE

Some nitrate loss from agricultural activities seems

inevitable even with good management practices, especially in areas with coarse-textured

soils or shallow soils over fractured bedrock. From a planning perspective, therefore,

the solutions may lie in keeping new agricultural operations out of the zone

of influence for existing wells, and in avoiding the location of new private

or public wells in areas where nitrate contamination in groundwater has already

occurred.

The 2002 UW-Extension publication titled “Planning

for Natural Resources - A Guide to Including Natural Resources in Local Comprehensive

Planning” gives more details about the following implementation tools that

can be used to address natural resources issues in the planning process:

- Education Tool: Education

and citizen participation in making land use decisions, implementing land use

goals, and taking private actions aimed at limiting nitrate contamination of

groundwater.

- Environmental Assessment Tool: Environmental

assessment requirements within zoning or subdivision ordinances to provide detailed

information about the potential effects of proposed development on nitrate levels

in groundwater, or to ensure that suitable sources of water for private wells

are available on a proposed development site.

- Facility Planning Tool: More

detailed facility plans for potential contamination sources, such as spill containment

plans for potential nitrate sources.

- Regulatory Tools, including:

- Zoning

- Performance zoning, which outlines

general water quality goals that developers or other landowners can meet by a

variety of methods.

- Overlay zoning, which allows special

regulations of sensitive environmental areas such as wellhead protection districts

or groundwater recharge areas.

- Planned Unit Developments may allow

developers to vary some of the standards in local zoning ordinances to allow

innovative approaches that may better protect groundwater.

- Subdivision regulations could include requirements

for adequate and safe water supply and wastewater disposal and treatment facilities,

as well as addressing land suitability and environmental and design issues. (For

further information on subdivisions’ impacts on groundwater, see footnote

#3).

- Increased nitrate treatment by onsite wastewater

systems could be encouraged with financial incentives or density bonus incentives,

although the current Wisconsin Administrative Code (Comm 85.035) does not allow

such systems to be required.F23

- Density transfers can allow the transfer

of development rights from one parcel that a community wants to protect to another

parcel where the community wants development to occur.

- Acquisition Tools, including:

- Outright purchase of land needed for groundwater

protection by communities or non-profit conservation organizations.

- Conservation easements could limit land

uses to those not likely to contaminate groundwater with excess nitrate.

- Purchase of development rights can protect

land from development with certain types of groundwater-contaminating activities

while allowing the landowner to retain ownership of the land and the ability

to sell or transfer it at any time.

- Eminent domain allows government to take

private property for public purposes with compensation to the owner, even without

the owner’s consent. This tool could be used to acquire critical groundwater

protection areas.

- Fiscal Tools, including:

- Capital improvement programs that help a

community plan and budget for capital improvements such as water supplies and

wastewater treatment facilities.

- Impact fees can require new developments

to pay for improvements needed to serve that development.

- WDNR may provide grant or loan programs

to help communities assess and meet their needs in areas involving sensitive

natural resources such as groundwater.

A community could also consider hiring a specialist

to evaluate areas where groundwater is particularly vulnerable and to identify

agricultural and other strategies to minimize nitrate leaching.

PESTICIDES

- A 2002 study estimated that 18%

of private drinking water wells in the region of Wisconsin that includes Iron

County contained a detectable level of an herbicide or herbicide metabolite.

Pesticides occur in groundwater more commonly in agricultural regions, but can

occur anywhere pesticides are stored or applied.F24

- There are no atrazine prohibition

areas in Iron County.F25

Definition and Use

A pesticide is any substance used to kill, control

or repel pests or to prevent the damage that pests may cause.F26 Included

in the broad term “pesticide” are herbicides to control weeds, insecticides

to control insects, and fungicides to control fungi and molds. Pesticides are

used by businesses and homeowners as well as by farmers, but figures for the

amounts and specific types of pesticides used are not generally available on

a county-by-county basis.

A 2005 report indicates that approximately 13 million

pounds of pesticides are applied to major agricultural crops in Wisconsin each

year, including over 8.5 million pounds of herbicides, 315,000 pounds of insecticides,

one million pounds of fungicides, and 3 million pounds of other chemicals (this

last category applied mainly to potatoes).F27 The report also shows

that herbicides are used on 100% of carrots for processing, 99% of potatoes,

98% of cucumbers for processing, 98% of soybeans, 97% of field corn, 89% of snap

beans for processing, 87% of sweet corn, and 84% of green peas for processing.

Insecticides are used on 97% of potatoes, 96% of carrots, and 88% of apples.

Fungicides are used on 99% of potatoes, 88% of carrots, and 89% of apples.

Crops by acreage grown

in Iron County in 2005-06

and average pesticide application per crop in Wisconsin.

The number of pounds of pesticide applied per acre

in Wisconsin varies greatly by crop, from 28 pounds/acre for apples to less than

one pound/acre for oats and barley (see table below).F27

Total pounds of pesticides

applied to

major crops in Wisconsin, 2004-2005.

|

Crop

|

Acres

|

Total pounds

of pesticides applied

|

Pounds of pesticides

applied per acre

|

| Apples |

5,800

|

163,300

|

28

|

| Potatoes |

68,000

|

950,000

|

14

|

| Tart cherries |

1,800

|

14,700

|

8

|

| Carrots for processing |

4,200

|

29,400

|

7

|

| Snap beans |

76,000

|

251,600

|

3

|

| Sweet corn |

88,400

|

198,000

|

2

|

| Field corn |

3,800,000

|

6,503,000

|

2

|

| Green peas for

processing |

30,200

|

33,500

|

1

|

| Soybeans |

1,610,000

|

1,770,000

|

1

|

| Cucumbers for processing |

4,600

|

3,800

|

1

|

| Cabbage, fresh |

4,400

|

2,700

|

1

|

| Barley |

55,000

|

5,000

|

<1

|

| Oats |

400,000

|

25,000

|

<1

|

Atrazine Prohibition Areas

As of 2006, the WDATCP has prohibited the use of the

popular corn herbicide atrazine on 102 designated atrazine prohibition areas

in Wisconsin, covering about 1.2 million acres.F25 There

are no atrazine prohibition areas in Iron County.

Environmental fate of pesticides

Once a pesticide is applied, it ideally will harm

only the target pest and then break down through natural processes into harmless

substances.

However, the actual fate of pesticides in the environment

may include evaporation into the air; runoff into surface water; plant uptake;

breakdown by sunlight, soil microorganisms or chemical reactions; attachment

to soil particles; leaching into groundwater; or remaining on the plant surface

and removal at harvest.

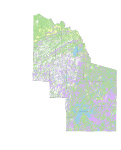

The WDATCP conducted a private well water study from

2000-2001, looking for some of the most commonly used herbicides in Wisconsin.F29 From

that study, the statewide estimate of the proportion of private drinking water

wells that contained a detectable level of a herbicide or herbicide metabolite

(breakdown product) was 37.7%. The map at the right shows the estimated percentage

of wells containing herbicide or herbicide metabolites by region. The study did

not look at less commonly used herbicides or any insecticides or fungicides.

WDATCP is doing a similar study in 2007 that includes analysis for a greater

number of pesticides.

READ MORE

How much of a pesticide application will leach to

groundwater depends upon four factors:F30

- pesticide properties such

as high water solubility, low adsorption (the ability of a pesticide to attach

to soil particles), and high persistence (how long it takes for the chemical

to degrade)

- soil characteristics such

as high permeability and porosity, low soil compaction, low amounts of organic

material, and high amounts of sand and gravel content

- site conditions such

as shallow depth to groundwater, high amount of precipitation, and excessive

irrigation

- management practices such

as poor timing of pesticide application, not incorporating the pesticide into

the soil, poor handling of the chemical, and solely relying on chemicals for

pest control

Determining which pesticides are in groundwater at

a given location and time is difficult and can be expensive. A pesticide test

generally looks for a single chemical, or more commonly, a broad group of chemicals,

but not all pesticides are detected by any one test. Pesticides break down over

time into metabolites which may not have the same testing method as the parent

compound. Further, some pesticides do not have approved testing methods, so they

cannot be measured in water.

Health effects of pesticides

READ MORE

The health effects of pesticide exposure vary by pesticide.

For example, atrazine, a common corn herbicide, has been linked to weight loss,

cardiovascular damage, retinal and some muscle degeneration, and cancer when

consumed at levels over the drinking water limit for long periods of time.F31 Long-term

exposure to alachlor, another herbicide, is associated with damage to the liver,

kidney, spleen, and the lining of the nose and eyelids, and cancer.F32 Only

about 30 pesticides currently have health-based drinking water limits in Wisconsin,

so occasionally, pesticides are detected in drinking water, but their harmful

levels or health effects are unknown. Also unknown are the health effects of

a combination of pesticides in drinking water, even at levels below the drinking

water limit for any one of the pesticides.

To learn more about pesticides, please see

Planning

READ MORE

Goals for groundwater protection from pesticides

may include:

- Determine what pesticides are being

used and where. Test wells in these areas for these pesticides and their metabolites.

- For pesticides with established drinking

water limits, keep concentrations below the drinking water limit.

- Encourage and support the use of organic

farming methods in the county.

- Limit use of lawn pesticides (perhaps

by limiting lawn size).

Implementation tools

Because of differences in pesticides, soils, and management

practices, knowing which crops are grown in an area alone does not accurately

indicate the risk to human health. However, knowing where pesticide use is likely

to be heaviest may be useful in comprehensive planning if one of the goals is

to minimize human exposure to potential contaminants in the environment.

Implementation tools that can be used to address groundwater

issues in the planning process may include:

- Education Tool: Education

and citizen participation in making land use decisions, implementing land use

goals, and taking private actions aimed at limiting pesticide contamination of

groundwater.

- Private well water testing and education

programs offered by the University of Wisconsin – Extension can increase

public awareness of pesticide contamination in groundwater and local government

officials’ interest in taking proactive planning steps to protect groundwater.

In Iowa County, for example, town officials began using groundwater information

collected through such programs as criteria for siting new facilities and developments.F15

- The University of Wisconsin – Madison

and UW - Extension have many educational programs in place to help farmers limit

the use of pesticides and pesticide losses to the environment,F33 such

as the Integrated Crop and Pest Management (ICPM) program, which can be accessed

and implemented locally through the county Extension office.

- Environmental Assessment Tool:

Environmental assessment requirements within zoning or subdivision ordinances

to ensure that suitable sources of water for private wells are available on a

proposed development site.

- Facility Planning Tool:

More detailed facility plans for potential contamination sources, such as spill

containment plans for potential pesticide sources.

- Regulatory Tools: including

- Zoning

- Performance zoning, which outlines general

water quality goals that developers or other landowners can meet by a variety

of methods.

- Overlay zoning, which allows special regulations

of sensitive environmental areas such as wellhead protection districts or groundwater

recharge areas.

- Density transfers can allow the transfer

of development rights from one parcel that a community wants to protect to another

parcel where the community wants development to occur.

- Acquisition Tools, including:

- Outright purchase of land needed for groundwater

protection by communities or non-profit conservation organizations.

- Conservation easements could limit land

uses to those not likely to contaminate groundwater with pesticides.

- Purchase of development rights can protect

land from development with certain types of groundwater-contaminating activities

while allowing the landowner to retain ownership of the land and the ability

to sell or transfer it at any time.

- Eminent domain allows government to take

private property for public purposes with compensation to the owner, even without

the owner’s consent. This tool could be used to acquire critical groundwater

protection areas.

- Fiscal Tools: including

WDNR grant or loan programs to help communities assess and meet their needs in

areas involving sensitive natural resources such as groundwater.F34

- Incentive Tools: Incentives

from local governments to grow groundwater-friendly crops including

- A community could identify agricultural

lands in the recharge area for its wells and provide various incentives for farmers

to enter into cropping agreements to limit pesticide inputs.

- Woodbury County, Iowa offers property tax

rebates to farmers who switch to organic methods.F35

- A community may hire a specialist to evaluate

areas of high pesticide use and develop possible pesticide management strategies

or promote low-pesticide agricultural systems or organic farming systems which

forbid the use of synthetic pesticides.

- A community may encourage food processors

that purchase organic or groundwater friendly foods to locate or form in the

area.

ARSENIC

- 100% of

1 private well samples collected

in Iron County met the health standard for arsenic.F43

Of the 1 water samples analyzed for arsenic

in Iron County, no samples have detectable arsenic and no samples are greater

than the recently reduced drinking water limit of 10 µg/L (micrograms per

liter, or parts per billion).F44

Most private wells in the county have

unknown arsenic levels.

Introduction

Arsenic is an element that occurs naturally in some

of Wisconsin’s aquifers and may contaminate well water drawn from those

aquifers. It is a particular problem in parts of the Fox River valley of northeastern

Wisconsin. However, arsenic has been detected in wells in every county in Wisconsin,

and arsenic concentrations greater than the drinking water limit of 10 µg/L

have been documented in 51 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties.F3

Health effects of arsenic

READ MORE

Drinking water with elevated levels of arsenic may

lead to a variety of health effects, including:F36 skin cancer, internal

cancers (bladder, prostate, lung, and other sites), thick, rough skin on hands

and feet, unusual skin pigmentation (dappling of dark brown or white splotches),

numbness in the hands and feet, circulatory disorders, tremors, stomach pain,

nausea, diarrhea, diabetes, depression.

Release of arsenic into groundwater

READ MORE

In northeastern Wisconsin, most of the arsenic is

found in a highly mineralized zone at the top of the St. Peter Sandstone aquifer.

The oxidation mechanism that releases arsenic occurs naturally in some cases,

but can also be triggered by either:F3

- Local and regional drawdown (drop in

water level) caused by increasing water use, which exposes the arsenic-bearing

zone to the atmosphere or

- Well construction techniques that introduce

oxygen into the aquifer.

However, revised WDNR drilling rules and special

well casing requirements have greatly reduced well construction problems.F44 Maps

are available from the WDNR that show special well construction and well

casing requirements by section for towns in Winnebago and Outagamie Counties.

In southeastern Wisconsin and the glacial moraines

of northern Wisconsin, the mechanism by which arsenic is released from geologic

materials is different. The arsenic is associated with iron oxides and is released

by natural reduction reactions that cannot readily be prevented or controlled.F3,

E38, E39 In such areas, alternatives are limited to treating water or using

another (often shallower) aquifer, if one is present and not contaminated with

nitrate or other human-induced contaminants.

Planning

READ MORE

Arsenic contamination could be addressed in comprehensive

planning in the following ways:

- Maps and other resources can be consulted

to determine the likelihood of arsenic contamination of drinking water supplies

in areas designated for residential development, and possible need for alternate

water supplies in those areas.

- Generalized

maps can be found on the WDNR web site for both public and private water

supplies sampled until 2000.

- Madeline Gotkowitz (mbgotkow@wisc.edu,

608/262-1580) at the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey has done

extensive research and public outreach on arsenic problems in Wisconsin’s

groundwater.

- Testing and education programs can

be conducted for owners of existing private wells in arsenic-prone areas to check

current arsenic levels in private wells, to advise about treatment options, and

to inform about ways to limit further arsenic release in the aquifer, where applicable.

- Restricting residential growth, encouraging

or mandating water conservation, or finding alternate water sources may be beneficial

in areas where oxidation is the primary method of arsenic release.

For further information on arsenic, please visit the WDNR

Arsenic in Drinking Water and Groundwater web site.

OTHER GROUNDWATER CONTAMINANTS

Information on volatile organic compounds, pharmaceuticals

and personal care products, and chloride.

READ MORE

Volatile Organic Compounds

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are a group of common industrial and household

chemicals that evaporate, or volatilize, when exposed to the air. Sources of

VOCs include a variety of everyday products such as gasoline, fuel oil, solvents,

degreasers, and dry cleaning solutions. When chemicals containing VOCs are spilled

or disposed of on or below the land surface some of the chemicals can be carried

down into the groundwater where they may pose a threat to nearby wells. Some

VOCs are quite toxic while others pose little risk. Health risks vary depending

on the type of VOC, but effects of long-term exposure can include cancer, liver

damage, spasms, and impaired speech, hearing, and vision.F40

Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products

The list of pharmaceuticals is long and includes such medications as tranquilizers,

pain killers, antibiotics, birth control, hormone replacement, lipid regulators,

beta blockers, anti-inflammatories, chemotherapy, antidiabetics, seizure control,

veterinary drugs, antidepressants, and other psychiatric drugs. There is a related

category of chemicals referred to as "personal care products" that

includes cosmetics, perfumes, soaps, sunscreens, insect repellants, and so forth.

The volume of pharmaceuticals and personal care products entering the environment

each year is about equal to the amount of pesticides used.

In 2000 the U.S Geological Survey conducted a nationwide

assessment of drugs in streams and groundwater. They picked locations likely

to be contaminated, but found pharmaceuticals in about 60% of groundwater samples.

Sources of discharge of pharmaceuticals to the environment include wastewater

treatment plants, onsite wastewater treatment systems, landfills, sludge and

manure spreading, and livestock feedlots. Why be concerned about traces of chemicals

that were designed to be consumed? We're only beginning to understand the health

effects. Because of the low concentrations, any effects are likely to appear

only after years of exposure. A real concern is that some of the drugs are endocrine

disruptors. Endocrine glands, such as the thyroid, pituitary or thymus send hormones,

such as adrenaline, estrogen or testosterone to specific cells stimulating certain

responses. There are hundreds of different hormones, and they are messengers

that regulate a multitude of normal biological functions, such as growth, reproduction,

brain development, and behavior. The delivery of hormones to various organs is

vital, and when the delivery, timing, or amount of hormone is upset, the results

can be devastating and permanent. Chemicals that are similar to hormones ("hormone

mimics") can fit onto the receptor sites on the target cells and either

block the real hormones or trigger abnormal responses in the cells. Scientific

studies have indicated links between endocrine disruptors and reproductive disorders,

immune system dysfunction, certain types of cancer, congenital birth defects,

neurological effects, attention deficit, low IQ, low sperm counts, and early

onset of puberty in girls.F41

Chloride

Chloride at levels greater than 10 mg/L usually indicate contamination by onsite

wastewater treatment systems (including water softener regeneration), road salt,

fertilizer, animal waste, or other wastes. Chloride is not toxic in concentrations

typically found in groundwater, but some people can detect a salty taste at 250

mg/L. Levels of chloride that are above what is typical under natural conditions

indicate that groundwater is being affected by human activities, and extra care

should be taken to ensure that land use activities do not further degrade water

quality.F42

return to top

|

| |

POTENTIAL

SOURCES OF CONTAMINANTS

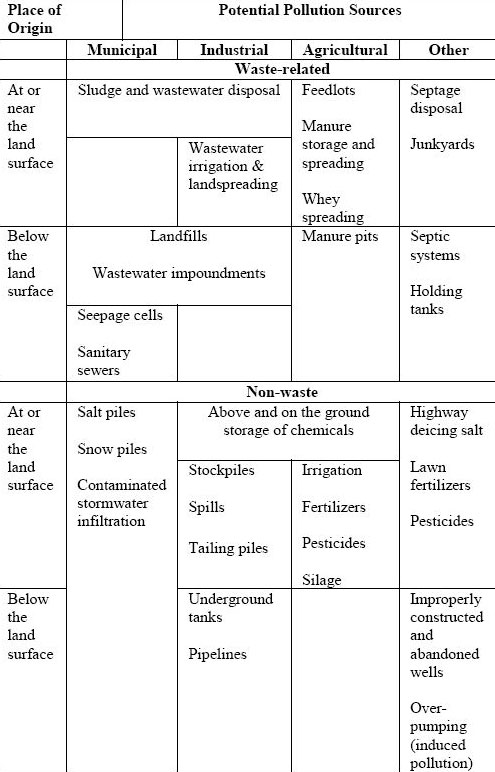

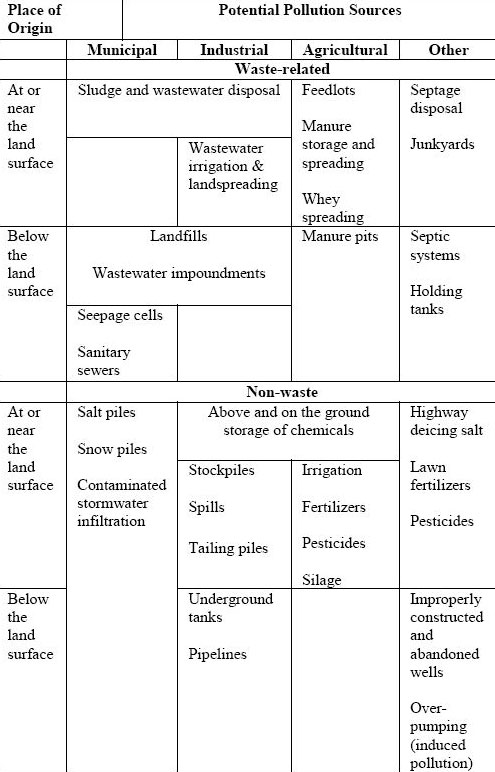

Since groundwater gets into the ground at the land

surface, it makes sense that what happens on the land surface can have impact

on groundwater. A great many land use activities have the potential to impact

the natural quality of groundwater, as shown in the table below.

A landfill may leach contaminants into the ground that end up contaminating groundwater.

Gasoline may leak from an underground storage tank into groundwater. Fertilizers

and pesticides can seep into the ground from application on farm fields, golf

courses or lawns. Intentional dumping or accidental spills of paint, used motor

oil, or other chemicals on the ground can result in contaminated groundwater.

The list could go on and on.G1 The

rest of this section provides county-specific information about potential sources

of groundwater contaminants.

ACTIVITIES THAT MAY CONTAMINATE GROUNDWATERG1

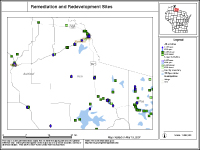

CONTAMINATED GROUNDWATER AND/OR SOIL

- There are 23

open-status sites in Iron County that have contaminated groundwater

and/or soil. These sites are composed

of 19 Leaking Underground Storage Tank (LUST) sites and 4 Environmental Repair

(ERP) sites.G2

Properties that were or are contaminated with hazardous

substances can be found using the WDNR's Bureau for Remediation and Redevelopment

Tracking System (BRRTS). The figure on the right shows the BRRTS map of contaminated

sites in Iron County. Royal blue diamonds on the map indicate open leaking

underground storage tank (LUST) sites which have contaminated soil and/or groundwater

with petroleum, which includes toxic and cancer-causing substances. However,

given time, petroleum contamination naturally breaks down in the environment.

Turquoise diamonds on the map indicate open environmental repair (ERP) sites

which are sites other than LUSTs that have contaminated soil and/or groundwater.

Examples include industrial spills or dumping, buried containers of hazardous

substances, and closed landfills that have caused contamination. More information

for the sites on the figure is available

online.

About the BRRTS

READ MORE

The WDNR Bureau of Remediation and Redevelopment Tracking System (BRRTS) contains information about locations at which there have been releases of hazardous or potentially hazardous substances to the lands, waters, or air of the State of Wisconsin. Degradation of groundwater quality is one of the primary concerns at BRRTS sites, but soil, vapor, air, and surface water contamination are also areas of concern.

What is a Hazardous Substance?

READ MORE

A Hazardous Substance is defined in s. 292.01, Wis. Stats., as “any substance or combination of substances, including any waste of a solid, semisolid, liquid or gaseous form which may cause or significantly contribute to an increase in the mortality or an increase in serious irreversible or incapacitating reversible illness, or which may pose a substantial present or potential hazard to human health or the environment because of its quality, concentration or physical, chemical or infectious characteristics. This term includes, but is not limited to, substances that are toxic, corrosive, flammable, irritants, strong sensitizers or explosives as determined by the WDNR.”

Types of hazardous substance occurrences or discharges that are documented in the BRRTS database include:

- Abandoned Container (AC) – an abandoned container with potentially hazardous contents has been inspected and recovered, but discharge to the environment has not occurred.

- Leaking Underground Storage Tank (LUST) – a leaking underground storage tank has contaminated soil and/or groundwater with petroleum. Petroleum products contain cancer-causing and toxic substances, but may biodegrade, or break down naturally in the environment, over time.

- Environmental Repair (ERP) – sites other than LUSTs that have contaminated soil and/or groundwater. Industrial spills or dumping, buried containers of hazardous substances, closed landfills, and leaking above-ground petroleum storage tanks are potential ERPs.

- Voluntary Party Liability Exemption - an elective process in which a property owner conducts an environmental investigation and cleanup of an entire property and then receives limits on future liability for that contamination.

- Spills – discharges of hazardous substances, usually cleaned up quickly.

For further information, see the BRRTS

web site glossary.

How to use BRRTS information in comprehensive planning

READ MORE

BRRTS information provides a snapshot of contaminated sites that need to be considered when developing land use plans. Steps toward incorporating BRRTS information into a comprehensive plan include

- Inventory contaminated sites and identify their status.

The summary document prepared for each county on this web site lists BRRTS sites that are still open. Other sites of interest may include closed sites and conditionally closed sites on the BRRTS list, or sites in the community that have not yet been investigated by WDNR but are suspected to have had hazardous releases in the past.

- Identify land use restrictions and deed restrictions assigned to contaminated properties. Land use restrictions are placed on BRRTS sites to protect public health and the environment. A BRRTS site that is “closed” and requires no further cleanup action may still have residual soil or groundwater contamination. If it does, it is moved to the GIS Registry of Closed Remediation Sites. Sites on the Registry have restrictions that may include

- site maintenance plans

- requirement for WDNR approval before new well construction

- special required well construction features

- special precautions when excavating soils

Details about such restrictions are available in the GIS

Registry of Closed Remediation Sites fact sheet.

- Identify properties on which redevelopment would be desirable for the community. Communities may be eligible for assistance in redeveloping contaminated or formerly contaminated industrial or commercial sites that are abandoned, idle or underused through WDNR initiatives aimed at brownfield redevelopment. Helpful tools for redevelopment include

- environmental liability exemptions

- financial incentives

- WDNR assurance letters

Details on programs to help with brownfield redevelopment are found in the WDNR publication Ironfields and Comprehensive Planning

A list

of WDNR staff contacts to assist with various aspects of remediation and redevelopment of contaminated sites, including assistance grants for local governments, is available online.

For more information, please see Environmental

Contamination – The Basics, WDNR publication PUB-RR-674 July, 2004.

CONCENTRATED ANIMAL FEEDING OPERATION (CAFO):

- There are no concentrated

animal feeding operations in Iron County.G3

By

definition, CAFOs have greater than 1000

animal units. CAFOs are required under

their Wisconsin Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (WPDES) permits to practice

proper manure management and ensure that adverse impacts to water quality do

not occur. Permit applicants must submit detailed information about the

operation, a manure management plan, plans and specifications for all manure

storage facilities, and a completed environmental analysis questionnaire. Once

a WPDES CAFO permit is issued, operators must comply with the terms of the permit

by following approved construction specifications and manure spreading plans,

conducting a monitoring and inspection program, and providing annual reports.

Other

potential groundwater contaminants from agriculture include fertilizers and

pesticides. Large amounts of nitrogen fertilizers are used when fields are planted

continuously with corn, and they can leach into groundwater as nitrate.

For more information, please visit the WDNR

CAFO web site.

LICENSED LANDFILLS

- There are no licensed

landfills in Iron County.G4

The county may have additional facilities listed in

the Registry of Waste Disposal Sites, available from the WDNR, that includes

active, inactive, and abandoned sites where solid or hazardous wastes were known,

or were likely, to have been disposed. The inclusion of a site on the Registry

does not mean that environmental contamination has occurred, is occurring, or

will occur in the future. The Registry is intended to serve as a general informational

source for the public, and State and local officials, as to the location of waste

disposal sites in Wisconsin.

About Wisconsin's Solid Waste Management Program

READ MORE

Wisconsin's solid waste management program has been in place for over 30 years. In the first two decades of the program, efforts were primarily directed toward: licensing existing solid waste facilities; closing poorly located or operated facilities; and ensuring that new solid waste facilities were properly located, designed, constructed, operated, closed, and maintained. During this period, the vast majority of municipal and industrial solid waste generated was landfilled.

In the 1990s, things began to change. Wisconsin's Recycling Law was passed in 1990, with most of the requirements taking effect in 1995. In 1997, ch. NR 538, Wis. Adm. Code was promulgated, facilitating the beneficial use of industrial byproducts. These two milestones resulted in significant and still-increasing quantities of waste being diverted from landfills.

As of the summer of 2001, Wisconsin has the following

numbers of licensed/regulated facilities in operation: 44 municipal solid waste

landfills; 41 industrial waste landfills; 36 construction and demolition waste

landfills; 1,446 solid waste transporters; 78 transfer stations; 64 processing

facilities; 6 municipal waste combustors; 148 composting facilities (mostly yard

waste); and 125 woodburning sites.G5

The solid waste program strives to ensure proper management of solid waste and works with its customers to increase waste reduction, reuse, and recycling. For more information on solid waste management in Wisconsin, see the Future of Waste Management Study completed in 2001.

A complete

list of licensed landfills in Wisconsin for 2007 can be found online.

More

information on solid waste is available from the WDNR.

SUPERFUND SITES

- There are no Superfund

sites in Iron County.G6

What is Superfund?

READ MORE

In 1980, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), commonly known as the Superfund law. The Superfund law created a tax on the chemical and petroleum industries. The tax went into a trust fund to help pay for cleaning up abandoned or uncontrolled waste sites.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administers the Superfund trust fund and works closely with state and local governments and tribal groups to remediate sites that may endanger public health or the environment. The contamination at many of these sites was created years ago when environmental regulations were virtually nonexistent and companies dumped or emitted hazardous materials freely into the environment. Years later the threat to humans and the ecosystems remains so great that the sites need to be cleaned up.

Unfortunately, since much of this contamination was caused so many years ago, it can be hard to find the parties responsible, or the parties responsible may be unwilling or unable to pay for the cleanup. In these cases, the Superfund trust fund can be used to pay for most of the cleanup process. States must pay for a portion of such cleanups.

CERCLA also provides EPA with enforcement tools to compel those responsible for causing the contamination to pay for the cleanup, including the issuance of administrative orders. If the trust fund is used, then EPA and the state may go to court to recover their expenditures from those who are responsible.G7

return to top

|

| |

NEXT STEPS

Now that you’ve inventoried groundwater data

and analyzed it, what’s next? How do you use this information to lead to

on-the-ground actions?

Now comes the key part of the planning process, where

it’s important to involve as many community members as possible to develop

and implement a plan of action to protect groundwater. The following sections

of this web site are intended to help your community move forward together to

protect groundwater.

return to top

|

|

Land

use affects nitrate concentrations in groundwater. As shown in the figure on

the right, an analysis of over 35,000 Wisconsin drinking water samples found

that drinking water from private wells was three times more likely to be unsafe

to drink due to high nitrate in agricultural areas than in forested areas. High

nitrate levels were also more common in sandy areas where the soil is more

permeable.

Land

use affects nitrate concentrations in groundwater. As shown in the figure on

the right, an analysis of over 35,000 Wisconsin drinking water samples found

that drinking water from private wells was three times more likely to be unsafe

to drink due to high nitrate in agricultural areas than in forested areas. High

nitrate levels were also more common in sandy areas where the soil is more

permeable.